Paradise found

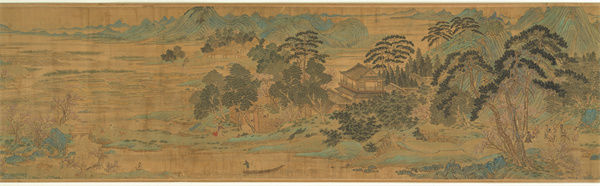

This 17th-century painting, The Peach Blossom Spring, is inspired by a fable of the same name, written by Chinese history's most famous recluse Tao Yuanming (365-427).[Photo provided to China Daily]

"It is the time for cherries and bamboo shoots in Jiangnan/the moist greens are refreshing/As the rain falls, peach blossoms arrive with the rising water/the crops sprout as spring hurries into the season."

The poem, from 16th-century painter-calligrapher Wen Peng, was composed to accompany the painting of his friend Qian Gu — both active members of a coterie of literati-artists formed around Wen's father.

Wen Zhengming (1470-1559), the old man, had once been recognized as a young genius, before spending four years in Beijing, capital of China during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), to pursue what seemed to be a promising career that he had long deserved. What happened at the end of that stint was that he packed up and went back home to the city of Suzhou, located in Jiangnan — the southern part of the Yangtze River Delta.

Over the ensuing 32 years, the senior Wen turned himself into something of a cult figure. On top of his talent was the public perception of him as a man of high moral standards who disavowed the seedy side of politics in favor of a secluded existence in the garden abode he built for himself.

Yet one thing was unignorable: Wen Zhengming's self-imposed exile, as those orbiting around him might wish to call it, was lived out not in sheer harshness, but amid the many enjoyable things that Jiangnan had to offer, including its spring.

"For Wen Zhengming and his followers, the spring of Jiangnan was common subject matter, a shared language which allowed them to interact and bond on paper," says Clarissa von Spee, curator of an ongoing exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art that examines, among other things, the crucial role this region played in China's cultural history.

The Wen Peng painting, on view at the exhibition, depicts the classic Jiangnan countryside: paddy fields running along stretches of water, lined by flowering plum trees and dotted with boats and bridges. It shares gallery space with a number of other similarly themed artworks, including one by the much-adulated Wen Zhengming.

"They clearly identified with the land," she says.

A solitary state

In fact, Jiangnan, whose geographical borders had been shifting according to Von Spee, was once a land of exile in the true sense of the word. "During the 3rd century BC, Qu Yuan, a member of the aristocracy from the state of Chu, was banished for disagreeing with what he saw as a corrupt court. In written sources, we find the words 'Jiangnan' for the region he was expelled to — one of the earliest appearances of the term," says Von Spee.

It was during China's Warring States Period (475-221 BC) which, as its name suggests, was marked by territorial wars fought among multiple states. One of them, the state of Qin, eventually crushed all others, and its king, Ying Zheng, subsequently became the first emperor of a unified China, known as Qinshihuang.

While the triumph of Ying Zheng made Jiangnan part of a centralized Chinese dynasty for the first time, the tragedy of Qu Yuan, who drowned himself in utter disillusionment in around 278 BC, infused his land of exile with a nobleness that appealed to generations of Chinese, both morally and aesthetically.

One thing must be noted: The term "Jiangnan" cited here should not be confused with the "Jiangnan" as we know it today. Here, "Jiangnan" refers to a solitary part of the state of Chu where the Xiangjiang River and its several tributaries converged, south of the middle — instead of lower — reaches of the Yangtze River. And it had a more popular name, Xiaoxiang, which was "thought of as a place of reclusion and longing in view of its natural beauty", to quote Von Spee.

Such was the hold of Xiaoxiang on people's imagination that the Northern Song emperor Huizong (1082-1135), a highly accomplished painter-calligrapher, had once sent a court painter out to explore the region. That was before the founding of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) by a son of Huizong, who moved the empire's capital southward, from Central China to the fertile land of the lower Yangtze Delta. The legend of Xiaoxiang continued, but there seemed to be no need for the Southern Song emperors to look beyond their immediate surroundings.

From shimmering lakes and sinuous waterways, to low-lying marshy basins and lush hills, everything Xiaoxiang was supposed to have, Jiangnan had it — and still does today. The two ideas started to merge, especially for literati-artists like Wen Zhengming and his group, who considered Jiangnan their physical and spiritual homeland.

Elite retreat

Paintings based on the Jiangnan scenery and attributed instead to Xiaoxiang were created in such great numbers starting from the early 12th century that many of them eventually found their way to Japan and the Korean Peninsula, where the misty, water-saturated views were interpreted as giving visual expression to Chan (Zen) Buddhism's belief in the illusory nature of reality.

Buddhism first spread to Jiangnan following an exodus from northern China that took place in the early 4th century, upon the transition between the Western and Eastern Jin dynasties (265-420).

The political upheaval that continued largely unabated for the next three centuries bred discontent and disillusionment. A sense of escapism started to develop among members of the society's educated elite, who turned to nature for consolation. Tao Yuanming (365-427), a politician-turned-poet who lived his life in Jiangnan during the time of the Eastern Jin, was probably the most famous of them all.

The Cleveland Museum of Art exhibition features a portrait of Tao from the 17th-century painter Chen Hongshou, who was also active in Jiangnan, testifying to Tao's lasting cultural relevance.

Other hermits were getting their fair share of the attention, too. Also on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art, two rubbings, made of murals from an excavated 5th-century tomb in the Jiangnan region's city of Nanjing, depict a gathering of seven men known collectively as "the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Groves". Keeping in mind that the gathering actually took place between 240 and 249 in today's Jiaozuo city, Central China's Henan province, the discovery of the murals, two centuries down the line and more than 600 kilometers away, stands as another example of Jiangnan's adoption of classical motifs from the country's cultural history.

The bamboo groves, as Wen Peng's poem had clearly described, grew just as lush, if not more so, in Jiangnan, where they could have served, for those seeking mental refuge, as a reminder of the bygone sages.

This image of Jiangnan as the perfect retreat was further strengthened during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), founded by the Mongols, with Beijing as its capital. Beijing remained a political center for the next 600 years, serving as the capital for both Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

The Mongol rule was met, not surprisingly, with initial resistance, especially from the literati group which was composed overwhelmingly of ethnic Han people. Harboring misgivings toward the new regime, some chose to live in half-retirement amid the idyll of Jiangnan.

One of them, Wang Meng, born into a distinguished Jiangnan family, withdrew, at one point, into the mountains north of Hangzhou, the one-time capital of Southern Song Dynasty, calling himself Woodcutter of the Yellow Crane Mountain.

At the Cleveland museum show, Wang the self-claimed woodcutter, represented by a landscape, reunites with his scholar-official uncle Zhao Yong, who envisioned himself as a fisherman lost in pastoral Jiangnan. Given the fact that Zhao Yong's father, the hugely influential painter-calligrapher-art theorist Zhao Mengfu, had occupied key positions within the Yuan government, the painting reads like a personal statement that's more willful than sincere.

In fact, the Yuan rulers, through encouraging maritime trade, had done a great service to Jiangnan, whose exportation of silk and porcelain kept increasing during this period.

An idealist idyll

Another Yuan-era painter-calligrapher who had added a cultural layer to the land is Ni Zan (1301-74). Son of a wealthy Jiangnan family, he was forced, in his 40s, to abandon his estate due to floods, droughts and subsequent tax levies on the region's landholders. Dispersing his possessions and living intermittently on a houseboat, Ni witnessed the final years of the Mongol rule while continuing to make art.

Ni wrote, in poems collectively titled Three Odes to the Spring of Jiangnan:

"The spring breeze is petulant, and the spring rain urgent/pouring down like tears, moistening the river/Falling flowers regret leaving branches/Zither strings are plucked, to mourn the disarray of red (petals) and green (leaves) …"

A hand-scroll by Wen Zhengming titled Spring in Jiangnan, on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art, is believed to have been directly inspired by Ni's poems.

Although it doesn't seem quite so, says Li Lan, an ancient painting specialist from the Shanghai Museum, which owns the piece. "A sense of loss permeates Ni's words," she says. "Wen Zhengming, born in Jiangnan nearly a century after Ni's passing, dabbed his canvas with plenty of green and the occasional red for a lighthearted rendition of a breezy spring.

"Idealism — that's what it is," says Li. "And if you think about it, idealism is really the flip side of escapism."

Ask Tao Yuanming, Chinese history's much-celebrated recluse best remembered for his fable, The Story of the Peach Blossom Spring, written in 421, during a time of great political instability and national disunity.

The story is about a chance discovery by a fisherman of an ethereal utopia, where people lived in complete harmony with nature, unaware for centuries of the outside world. The fisherman, having haphazardly sailed into a river which carried him to the beginning of secret passage, emerged to "look into a landscape that must have looked like a Wen Zhengming painting", to use the words of Von Spee.

"On one hand, you have Tao Yuanming's peach blossom which is indicative of the springtime; on the other, you have these paintings of the Jiangnan spring which, complete with unspoiled nature and rice paddies, constitute an earthly paradise," she says.

The curator points to a Ming-era hand-scroll with a blue-green color scheme titled The Peach Blossom Spring, as well as a Qing Dynasty porcelain dish whose design illustrates the tale.

"Jiangnan is to China what Arcadia is to the West," she reflects. Derived from the ancient Greek province of the same name, the term Arcadia represents a vision of pastoralism and, as such, has long inspired Western art and literature.

According to Von Spee, the Peach Blossom theme saw its popularity soar during the Ming-Qing transition in the 17th century, another chaotic time that had persuaded more than a few to withdraw into the beauty and repose of Jiangnan. And when they did so, they had something — some people — in mind.

In 1652, a group portrait was painted to commemorate what some believe to be an imaginary gathering of six Jiangnan literati in 1636. While the figures were painted by a professional portraitist, the landscape was added on by Xiang Shengmo, who himself appears in the painting sitting at the back, to the right of the piece. The center of attention, not surprisingly, belongs to the red-clad Dong Qichang, the most prominent artist-cum-art theorist of the Ming Dynasty. Dong passed away in the autumn of that year.

In 1644, eight years before the creation of the group portrait, the last Ming emperor hanged himself in Beijing, and later, the Manchu rulers of the Qing Dynasty claimed for themselves the throne in the Forbidden City.

Xiang, 47 at the time, painted a self-portrait, placing himself in the middle of a typical Jiangnan landscape rendered completely in red. And it's no coincidence that zhu, the Chinese character for red, was the surname of the ruling family of Ming.

The man made no secret as to where his heart lay. Yet if he had lived long enough, he would have been able to see Dong, his mentor, being celebrated posthumously by successive generations of Qing emperors, who considered themselves inheritors of the country's immense and invaluable cultural heritage.

In the 1652 group portrait — on view at the Cleveland museum, both Xiang and Dong wear distinctive caps, the kind that was sported by literati of the Eastern Jin Dynasty.

"They were aware that they lived in the land of Tao Yuanming," says Von Spee.

-

Hangzhou welcomes massive addition to natural landscape

January 10, 2024

-

Hangzhou expects a 65.2% increase in tourist traffic over New Year holiday

December 29, 2023

-

Asian Games brings about great changes to Hangzhou

December 25, 2023

-

BRI 10 YEARS ON: Road to prosperity

October 16, 2023