One man's efforts in safeguarding China's ancient architecture

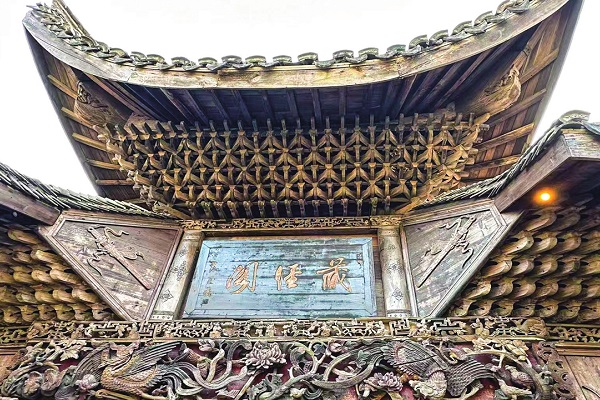

An ancestral hall from Wuyuan, Jiangxi Province Photo: Courtesy of Wang Baojin

Nestled within Hangzhou's Xixi National Wetland Park, Wujiawan Ancient Village is home to 60 restored buildings from the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911). Together, they represent a remarkable private effort to preserve the legacy of traditional Chinese architecture.

At the heart of the project is Wang Baojin, who has spent the past 27 years safeguarding this cultural heritage.

Later this year, the largest of these historic homes — a 1,200-square-meter former salt merchant's residence from the late Qing era, will open to the public free of charge as the Jiangnan Ming and Qing Ancient Architecture Museum.

"I believe the structural beauty of traditional Chinese architecture is unique," Wang told the Global Times. "It's like three-dimensional Chinese calligraphy and painting — something that can be passed down through generations."

His connection with ancient architecture began with a brief stop during a journey — dating back to 1998, when he first laid eyes on a historic building. He was 36 years old at that time.

Architectural devotion

Born in 1962, Wang attended college in the 1980s and moved from a village in East China's Zhejiang Province to work in Hangzhou, capital of the province. In 1998, a detour during a casual trip changed everything.

"The old house I saw — its carvings were exquisite and its structure was elegant. But someone was sawing the wood," Wang recalled. "I felt heartbroken."

Upon learning that the dismantled building could be reassembled, Wang purchased the remains and had them shipped to Hangzhou.

It marked the beginning of a lifelong obsession.

Wang had no formal architectural training. He started from scratch — studying independently, consulting craftsmen, and poring over books. He said he bought every book and photograph he could find on ancient Chinese architecture. "I wanted to figure out the lineage of ancient Chinese buildings."

"Every line feels like a brushstroke, and every piece of wood is like ink splashed on paper," he said, describing the beauty he sees in Chinese ancient architecture.

Wang rented an abandoned stone quarry, built a bamboo shelter, and began slowly reassembling the structure with the help of craftsmen. "It was like putting together a puzzle."

"The hard part," he added, "was when a piece was missing and I had no idea what it originally looked like." To resolve this, he visited similar houses in the area and used matching reclaimed materials to fill in the gaps.

Now, after decades of experience, he can determine what missing parts should look like simply by examining the structure.

"Practice makes perfect," he said.

Sense of urgency

What weighs on Wang is a sense of urgency — he can't afford to slow down in his search for ancient buildings. A delay could mean the sturdiest beams of a historic house would be cut into firewood and lost forever.

Back then, information was limited and often outdated. On several occasions, by the time he arrived, all that was left was rubble. "I frequently drove late into the night alone, and on multiple occasions, I had car accidents," he recalled.

To save these buildings, Wang printed stacks of business cards to hand out to antique collectors, asking to be contacted if they came across historic buildings to be demolished. When weekends weren't enough, he quit his job;when money ran low, he sold his house; and when that sum wasn't enough, he borrowed more from friends.

"As for my wife and daughter, I don't have money to give them — one of my greatest regrets," he said. "but they stood by me."

His daughter occasionally accompanies him to demolition sites. When she sees the restored and finished result, she also thinks her father is great, Wang told the Global Times.

Over the past 27 years, Wang scoured remote villages in East China's Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Anhui, and Jiangsu provinces, looking for vanishing ancient architecture.

The ancient buildings Wang acquired were first dismantled and numbered, then carefully transported from various locations to Hangzhou for sorting and storage before being restored.

As Wang acquired more old houses, he faced a growing dilemma: Where to store them all? His initial solution was to build a museum dedicated to ancient architecture. "I wrote to the Hangzhou city government, expressing my wish for future generations to understand what kind of homes ancient Chinese people lived in," he said.

In 2007, Wang received a response to his letter when the Hangzhou city government approved the reconstruction of the ancient buildings within Xixi National Wetland Park.

Rescued museum

Wang moved the beams, windows, ancestral halls, and opera stages stored in warehouses out for reconstruction. With thousands of components per house and no blueprints, relying solely on numbered parts, over the following years, he and his team of craftsmen eventually restored 60 Ming and Qing dynasty buildings.

Wang often described the restored houses to friends as "livable works of art."

The centerpiece, also Wang's favorite, is the building of the Jiangnan Ming and Qing Ancient Architecture Museum. Once the home of a Qing dynasty salt merchant, it took years to be fully reconstructed.

Every item inside was carefully salvaged in 2001 after Wang discovered a part of an ancient building being sold in an antique shop in rural Wuyuan, Jiangxi Province. He then located the original, ruined structure which was spread across seven households in various mountain villages.

Wang spent a week in Wuyuan, negotiating with each family one by one. The three-story house took several months to dismantle and was arranged for four extended trucks to transport the pieces back to Hangzhou.

"By reinstalling components bought from an antique shop into their original house, I saved an ancient building that had been dismantled and scattered. I feel a sense of accomplishment," Wang said.

The museum exhibits are still being arranged. All other 59 restored Ming and Qing dynasty buildings are also free to visit. Each house will have a plaque indicating its origin and architectural style to help visitors better appreciate its historical context.

Journey continues

Wang doesn't view these buildings as static relics of the past.

In 2019, the Wujiawan Ancient Architecture Village fully opened to the public.

"An empty house is a dead house," Wang said. "Without occupants, ancient buildings will deteriorate rapidly."

He established Craftsmen Street, and invited mostly young artisans of intangible cultural heritage to help revitalize Wujiawan. "I told them 'I offer you a free space where you can live forever and focus on your craft.'"

"Wujiawan used to be a forgotten place, but now more people are gradually coming. Many have quietly supported and helped me along the way. It shows that if you work earnestly and do meaningful things, people will see you. There is warmth in people's hearts, and I'm deeply touched by that," Wang said.

Back in his warehouse, another 60 buildings await restoration.

Wang said this will be the major project to which he plans to dedicate the rest of his life.

-

Visionary Pathway - Hangzhou Playbook

July 15, 2025