Xiling Seal Art Society: Stamps on culture

On Aug 27 and 29, the Chinese Embassy in the US and the Chinese Consulate General in New York hosted "Experience China – A Symphony of Stories on China-US People to-People Friendship."

The events featured music, cultural exchange and a lesser-known society that played a profound role in Sino-American friendship forged during the Chinese People's War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War.

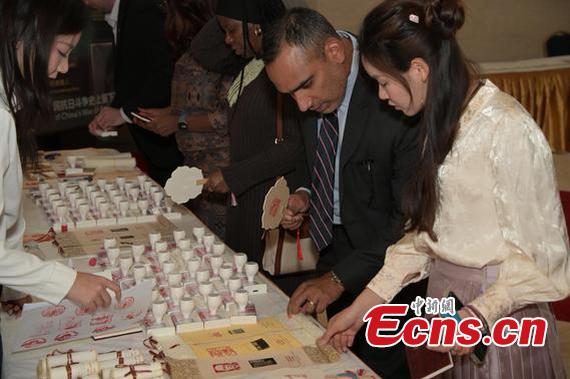

Seals by the Xiling Seal Art Society are displayed at Experience China – A Symphony of Stories on China-US People-to-People Friendship, Aug 27. [Photo Courtesy of Xiling Seal Art Society]

Of note was the unveiling of a long scroll titled "Echoes of Friendship Through Time" adorned with dozens of seals created by the prestigious Xiling Seal Art Society, one of China's most exclusive private academic institutions.

Each seal vividly recounts stories of Chinese and American solidarity in the fight against fascism. They depicted heroic episodes such as American missionary John Magee risking his life to document the Nanjing Massacre and the volunteer Flying Tigers squadron braving "The Hump" airlift over the Himalayas to deliver vital supplies to China.

Founded in 1904 as an organization dedicated to the art of seal carving and the study of inscriptions, the Xiling Seal Art Society is known for its high admission threshold, strict election procedures and longest presidential vacancy of any similar group.

Since the passing of its seventh president, Rao Zongyi, in 2018, the office has been vacant, the second-longest leadership hiatus in its history.

A combination of calligraphy and carving, seals have been used for centuries in China as unique personal signatures. Made of stone, wood or jade, they are pressed into red or black ink to stamp official documents or sign artwork, even today.

Visitors view an exhibition of works by honorary members of the Xiling Seal Art Society's Japan chapter in Tokyo on Aug 5. The show was jointly organized by the Xiling Seal Art Society and Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun. [Photo Courtesy of Xiling Seal Art Society]

But to become a member of Xiling, exceptional skill in seal carving is far from sufficient. A candidate must pass multiple stages that include a secret nomination by an existing member, anonymous evaluations of submitted works and a closed-door vote.

Its initiation ceremony for new members is still held at the Han Sanlao Stele on Gu Shan (Solitary Hill) in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. Dating to the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 CE), the tablet is the oldest surviving stone inscription of Han script. Using a calligraphy brush dipped in the city's West Lake, the new member must write an oath of induction.

In its 121-year history, the Xiling Seal Art Society, named after the famous Hangzhou bridge near its headquarters, has had no president for nearly 40 percent of its existence. This is due to the society's principle of "better no one than the wrong one" – the president must have both moral integrity and artistic excellence, as well as great respect from his peers. When famed calligrapher Qi Gong was nominated in 2005, members took two years to ratify it. Sadly, he passed away before taking office.

It is run very much the same today as when it was founded: there are no online applications, no membership fees and no commercial exhibitions. Members address each other as "brother." The elegant gatherings held on Solitary Hill during the Qingming (Tomb-Sweeping) and Chongyang (Double Ninth) festivals are some of the few left for China's cultural elites that are still untouched by commercialism.

The succession of presidents not only charts the society's growth but also embodies the resilience of traditional Chinese culture through modern history.

Carving Duel

It was late autumn in 1904 when four young men – Ding Fuzhi, Wang Fu'an, Ye Weiming and Wu Yin – sat around a weathered stone on the southern slope of Solitary Hill in Hangzhou. They brewed tea as they unrolled rubbings of ancient seals from the Warring States period (475-221 BC), carefully examining Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 CE) seals and newly acquired stone inscriptions. The breeze from the West Lake carried the mingled scents of tea and ink.

As the origin story goes, the group was bemoaning that the study of epigraphy and seal art had been in decline since the reigns of Qing Dynasty emperors Qianlong (1736-95) and Jiaqing (1796-1820), and agreed that something must be done. Wang Fu'an was the first to suggest they form a society right there on Solitary Hill. The four young men made a solemn pact, vowing to dedicate themselves to the art of seal carving.

On Nov 11, 1913, the then 69-year-old artist and scholar Wu Changshuo visited Solitary Hill with some of his students. Though used to viewing rare treasures, the society's collection of original Warring States jade seals left him astonished. He said that previously, he had only seen them in the Sixteen Gold Charms Studio Collection, a late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) compilation of rubbings primarily from the Zhou (1046-256 BC) and Qin (221-206 BC) dynasties, and never expected to see the real things in his lifetime.

The following spring, Wu Changshuo was unanimously elected as the society's first president. Under Wu's charismatic leadership, the society entered its first golden age. Wu regularly hosted cultural gatherings that attracted artists from across the country.

In 1920, the society built Guanle Tower on Solitary Hill, a two-story tower built to honor Wu's ancestor, Prince Jinzha of the State of Wu during the Spring and Autumn period (771-476 BC). Wu personally inscribed the name Guanle ("appreciating fine arts") – a reference to Jinzha's recorded commentary on Zhou Dynasty music and dance – into the lintel of the second story.

After Wu's death in 1927, the presidency fell vacant. But the members never wavered in their commitment, especially during wartime. When China's whole-nation War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression broke out in 1937, society member Ma Heng, then director of Beijing's Palace Museum (also known as the Forbidden City), ordered the society's cultural relics to be dispersed immediately to protect them.

Ding Fuzhi sewed the original Collected Seal Impressions of the Eight Masters of Xiling into the lining of his cotton coat. Wang Fu'an hid rubbings of the Han Sanlao Stele inside a specially made bamboo cane. Most dramatic of all was the rescue of a Warring States jade seal – young member Han Deng'an carried it in his mouth, nearly swallowing it while passing through a Japanese checkpoint. Thanks to their ingenuity and courage, the relics were preserved intact and later became the foundation of the society's post-war restoration.

In 1947, Ma Heng became the society's president. A skilled archaeologist, he led efforts to catalog the society's collection and promoted the publication of the Xiling Seal Society Series on Bronzes and Stones. In 1948, a high-ranking official attempted to seize the society's rubbings of the Mao Gong Ding, a bronze cauldron cast in the Zhou Dynasty whose 499 characters make up China's longest existing bronze inscription known to date. The society's Secretary-General Ruan Xingshan fled with the original rubbing to Hangzhou's Lingyin Temple, a sanctuary from the turmoil of the Chinese Civil War, handing over a high-quality replica instead. The deception remained a secret until decades later, when it was finally revealed after China's reform and opening-up in the late 1970s.

Following the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the society faced a new crossroads. In 1956, heated debate broke out among members over whether to accept integration into the State system. By then, President Ma Heng had passed away, and the position was once again vacant. Member Zhang Zongxiang, also an honorary director of the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, advocated for independence, while calligrapher-engraver Sha Menghai believed the society should adapt to the times.

The two men resolved their philosophical divide with a seal-carving duel: Zhang engraved the phrase "Better to be shattered like jade," his chisel work firm and forceful. Sha carved "Advancing with the times" in a fluid and graceful style. This fierce yet gentlemanly debate ended in mutual respect and set a tone of inclusion and balance for the society's future.

In 1963, Zhang Zongxiang assumed the presidency. He and key members such as painter Pan Tianshou hid important seal catalogues in the ancient books section of the Zhejiang Provincial Library, mixing them together with regular texts to protect them during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76).

Seal Diplomacy

In the early spring of 1973, the society received a letter from a Japanese calligraphy delegation. It was during the late stages of the Cultural Revolution and the Xiling Seal Art Society had long ceased formal operations. Yet the Japanese had specifically requested to visit this academic sanctuary, which they reverently called the "Holy Land of Seal Carving in the East."

That year, 72-year-old member Zhu Zuizhu received the notice and, with out delay, rode his bicycle through the narrow lanes of Hangzhou late into the night. He knocked on the doors of seven senior society members scattered across the city. Some were working as accountants in factories, while others taught art in public schools. A few were eking out a living by engraving tombstones.

At dawn, the group of society elders quietly gathered in a pavilion at the foot of Solitary Hill, where calligrapher and seal carver Zhu Zuizhu told his fellow members, "The society can exist without a signboard, but not without integrity."

On April 12, the Japanese calligraphy delegation led by Toan Kobayashi, calligrapher-engraver and president of the All Japan Seal Engravers Association, arrived as scheduled. Upon seeing the gray-haired Chinese seal carvers seated around the pavilion, and the ancient seals displayed on the tables, the entire delegation stood in solemn respect.

During the exchange, Kobayashi put forward a challenge: to carve the phrase "Though lands and seas divide us, we share the same moon and breeze." The couplet, by Japan's Prince Nagaya (684-729), refers to the Chinese monk Jianzhen, who is credited with traveling to Japan against incredible odds to introduce Buddhist teachings, as well as Chinese medicine, architecture and culture. He remains a symbol of China-Japan exchange to this day.

Liu Jiang, honorary president of Xiling and professor of China Academy of Art, volunteered to take up the challenge. His calloused right hand, still marked with chilblain scars from exposure to the cold, held the carving knife firmly. Every stroke carved into the seal stone released a mixture of blood and powdered stone. When the still-warm, blood-tinged seal was pressed onto the rice paper, the Japanese delegation rose and bowed in unison.

Even more moving was what followed. During the group's visit to the Han Sanlao Stele, Kobayashi suddenly straightened his robes and performed a full kowtow, pressing his forehead to the stone three times. This unprompted act of reverence was captured by a photographer and has since become an iconic moment in the history of Sino-Japanese cultural exchange.

Before leaving Hangzhou, the Japanese delegation gifted the society a rare copy of The Ancient Official Seals of Japan. On the inside cover in handwritten calligraphy was the inscription: "Let hearts speak through blade and brush, let stone and bronze bear witness." Kobayashi would later become an honorary vice president of the Xiling Seal Art Society.

This moment of cultural exchange would later be remembered as "seal diplomacy." More than a poignant episode in the society's century-long history, it became the first unofficial artistic exchange between China and Japan following the normalization of diplomatic relations. The seal engraved by Liu Jiang, bearing traces of his blood, remains carefully preserved in the society's archives today – an enduring testament to a friendship forged through art amid adversity.

In 1979, at the age of 85, Sha Menghai, a revered calligrapher, became the society's fourth president. Passionate about cultivating the next generation, Sha taught weekly classes to young members. Under his leadership, the society entered its second golden age.

In 1988, the Xiling Seal Art Society was designated a National Key Cultural Heritage Site. That same year, its 85th anniversary celebration drew over 300 artists from around the world. At the event, Sha spontaneously brushed the phrase "May seal and stone endure forever." It is regarded as one of his masterpieces.

Zhao Puchu, a prominent Buddhist leader and cultural figure, succeeded Sha in 1993 and led the society with renewed vigor. During its 90th anniversary celebration, Zhao invited artists from Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan – a first for the organization.

Then in 2011, Rao Zongyi, a 95-year old master of classical Chinese studies, took the helm. In 2009, the "Art of Seal Carving at Xiling Seal Art Society" was inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The Xiling Seal Art Society continues to thrive. At the foot of the Han Sanlao Stele, initiation ceremonies for new members are still held. For every Qingming and Chongyang festival, members from across China and the world return to Hangzhou, united by their shared reverence for the art.

From its founding by four young gentlemen to a society of some 500 members, the Xiling Seal Art Society went on to safeguard cultural relics during wartime and preserve China's intangible heritage. Its story resembles the bronze vessels it treasures most – weathered on the surface, yet brimming with heritage.

As calligrapher Sha Menghai once said: "Though seal carving may seem a minor craft, it touches upon the roots of our script and the foundation of our culture."

(Song Yimin is a culture researcher and Zhang Shu is a reporter of Zhejiang Daily Press Group)

-

Hangzhou to welcome global experts on ecology

September 17, 2025

-

Tidal surprise

September 10, 2025

-

In Zhejiang's capital, 8th Hangzhou International Day opens

September 5, 2025

-

Visionary Pathway - Hangzhou Playbook

July 15, 2025